Three Years That Broke American Politics (Part One)

1968: Backlash to the civil rights movement, and changes to the presidential nominating system

American politics feels broken. Not irretrievably, perhaps, but damaged enough so that there is legitimate fear about the future of democracy in the country. At the very least, it’s safe to say that politics in America is warped and dysfunctional compared to what it used to be.

But how did we get to this point?

I’ve given this question a lot of thought and it’s obvious our current dysfunction didn’t happen overnight. Just as your health is influenced by past lifestyle decisions, so it is with democracy. Today’s politics were shaped by events that took place years ago. It was the cumulative effect of various decisions that led us to this unfortunate point where a healthy democracy isn’t something we can just take for granted any more.

And while it’s true that Donald Trump has torched some Americans’ trust in elections in recent years, and smashed countless democratic norms along the way, it’s also true that numerous factors which wreaked havoc on our politics existed long before he rode down that escalator in 2015. So Trump may have thrown gasoline on the fires, but he didn’t start them all (apologies to Billy Joel).

With these thoughts in mind, I’m putting together a series of posts about three specific elections, going back a half-century, that I think symbolize how democracy in America has been pushed off track.

I’ve picked out two circumstances from each contest that negatively impacted the political landscape over time. Some of these were reckless actions taken by political leaders, driven only by a desire for power, while others were well-intentioned developments that had unforeseen consequences. But all of them, collectively, played a role in breaking the nation’s politics.

First up, 1968.

The quick 1968 backstory

The 1968 election took place against a backdrop of unrest. Lyndon Johnson chose not to run for re-election. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated. There were antiwar protests and race riots. And the Democratic convention saw a violent clash between police and protesters.

That fall, Richard Nixon narrowly defeated Hubert Humphrey in the presidential race, while the independent candidacy of segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace pulled in 13.5% of the vote, winning five southern states with 46 electoral votes.

Meanwhile, two significant developments from 1968 — one related to the presidential nominating system and the other to the civil rights movement — had far-reaching consequences that still roil American politics.

1968: Revolution in the presidential nominating system

As I’ve written previously, political parties for much of the 20th century selected presidential nominees via a hybrid system, with candidates sometimes running in primaries to prove their mettle but also needing support from party leaders to prevail at a nominating convention.

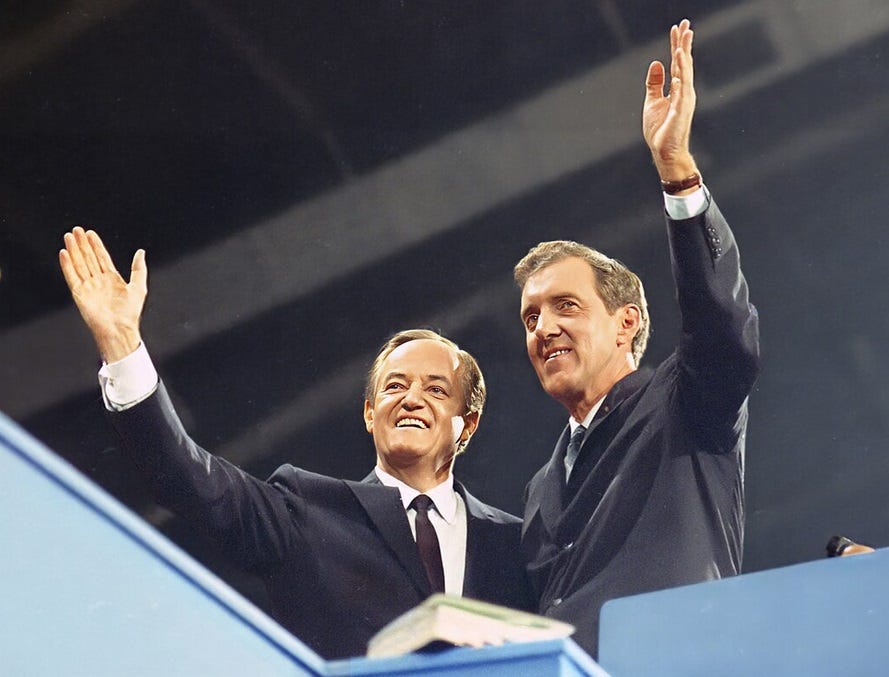

In 1968, however, Humphrey won the Democratic nomination solely with support from party leaders after not entering a single primary. This led to calls for changes in the system to put more emphasis on primaries and caucuses. New rules were thus instituted for the next election in 1972.

Today, this is portrayed as an act that finally took the nominating decisions out of the old smoke-filled rooms. Democracy expanded as voters gained power over party leaders. But it was also a momentous transformation in the way we select presidential candidates, as no other major democratic nation gives voters so much of a voice in choosing party nominees.

And the impact was seen immediately, as George McGovern won the 1972 Democratic nomination, a choice that almost surely wouldn’t have been made by party leaders.

Why this is still important today

This new emphasis on voters did make the process more democratic, which was the initial goal, as it forced candidates to gain popular support. And the arc of U.S. history has, over time, always been on the side of expanding democracy.

But every action has a reaction, and so it was with changes to the nominating process.

First, by moving the decision-making process away from party leaders at the convention and putting it in the hands of voters through primaries, what also happened was that power moved towards the loudest activists and the richest donors.

Moreover, while the smoke filled rooms are much maligned and no one particularly wants to go back to them, an unintended consequence of this new system was that it took away the power of the party to filter out individuals who might not make the best candidate or president.

It’s not like the parties have zero influence now — after all, Nancy Pelosi and others helped convince Joe Biden to step aside from his presidential campaign this summer — but the influence is minimal. In most cases the parties have little actual power in the nominating process. Just ask the GOP leaders who didn’t want Donald Trump to become the nominee in 2016. They were powerless to stop it.

Trump isn’t the first populist with authoritarian tendencies to gain a following in America. But in the past, these individuals had no way to get past the party filtering process. So someone like Huey Long or Joe McCarthy might have a passionate following, might even get elected governor or senator, but there was almost no way to win a presidential nomination. Likewise, a few decades ago Trump would also never have been nominated for president.

As parties have faded in importance, however, populists can now more easily gain power. Another reason for this is that the main filter between candidates and the public has been taken over by the media. And while the media may be well intentioned, news organizations are driven by a goal of attracting readers and viewers. It’s not the media’s job to promote the best possible president, but rather to find the most newsworthy candidates.

Not surprisingly then, in this media-driven and candidate-centered age, the individuals who stand out from the crowd, regardless of their resumes or abilities, are those who build the biggest followings. Voters are naturally drawn to those who dominate the news cycle, giving these candidates more of an advantage in nomination battles while often shutting out the opinions of party leaders. Sometimes this works out well, sometimes it doesn’t.

So, yes, it’s now the American way now to give voters a say in who parties should nominate for president. There are good things about this. But it’s also true that we may be less worried now about the future of American democracy if party leaders had retained control over the nominating system. We can’t put the genie back in the bottle, but we do need to acknowledge the impact this decision had on our politics.

1968: The civil rights movement and its backlash

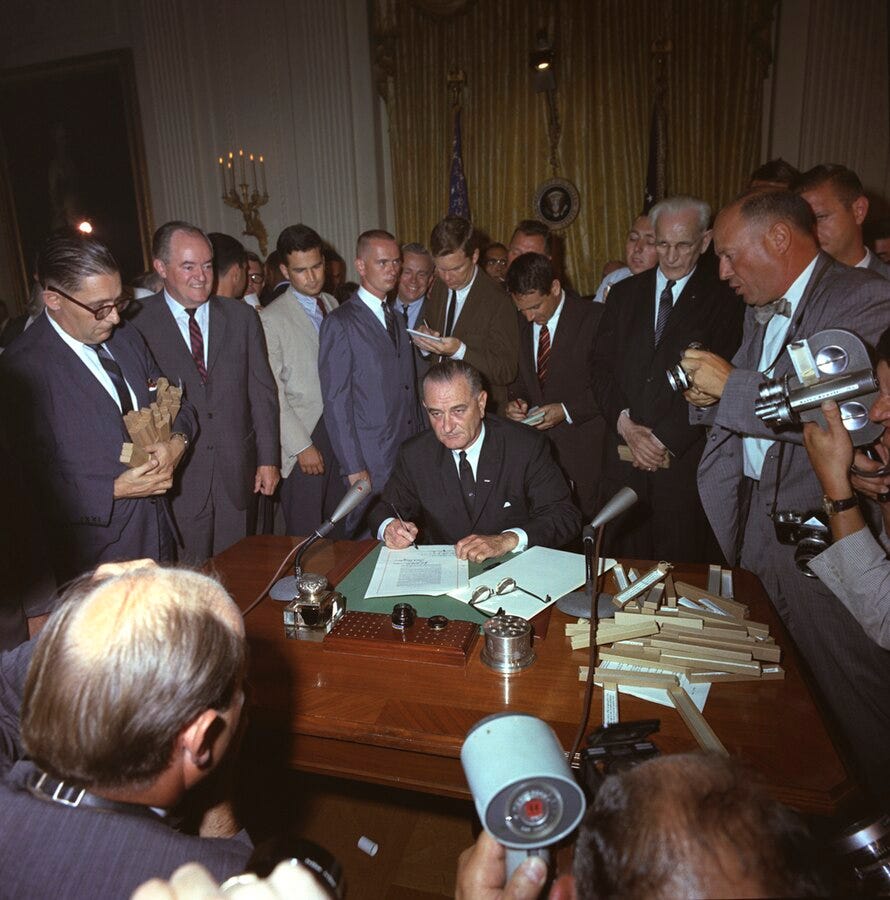

Before 1968 the Democratic Party had dominated politics in the South for more than a century. Cracks in this wall first appeared in 1948 as the party moved to support civil rights for Blacks, but President Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 finally triggered a seismic shift in American politics.

A sizeable bloc of conservative southerners were angry at Democrats for pushing this legislation. Some of them supported GOP nominee Barry Goldwater in 1964, but the anger coalesced more in the 1968 candidacy of George Wallace, a segregationist Alabama governor who ran under the banner of the American Independent Party.

With a slogan of “Stand up for America,” Wallace “tapped a current of grievance” by railing against civil rights laws, as well as government bureaucrats, antiwar protesters, activist judges, and the media. His politics were controversial, but he won 13.5% of the vote and five southern states. In fact, in a rebuke to the longstanding Democratic dominance in the South, every state in the region except for one voted for either Wallace or Nixon.

Why this is still important today

It took a few more cycles for this realignment to fully take hold, but the South has been a bastion of support for Republicans ever since. An even more important development, however, if we’re considering the impact on today’s polarized politics, was a messaging strategy that arose out of this backlash.

In 1972, the Nixon team took note of Wallace’s successes and some Nixon advisors recommended using Democratic support for Blacks as a way to peel away white voters. This famously became known as the Southern strategy and it involved playing up such topics as crime, welfare, or school busing to subtly play on anxiety about minorities and their impact on American culture. The goal was to pull conservative southerners and more working class whites into the GOP.

The strategy was successful enough that it was added to the party playbook for future elections. Even if the candidates themselves weren’t racist — and, at least on the presidential level, they usually were not — it was easy for campaigns to emphasize certain issues in a way that fostered racial angst. All that was needed was for voters to have some level of anxiety about losing what they saw as their traditional way of life. So when Ronald Reagan bemoaned welfare queens, or when the George H.W. Bush campaign aired the Willie Horton crime ad, voters got the message.

Lee Atwater, a GOP consultant and chairman of the Republican National Committee in the 1980s, bluntly explained the strategy back then. In previous decades, he said, politicians in some states could get away with an explicitly racist appeal. By 1968, however, they turned to code words like “forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff.” And by the 1980s the words changed again, so that when politicians talked about cutting government programs the assumption with many voters was that “blacks get hurt worse than whites,” according to Atwater.

A more explicit example of this was an ad that North Carolina GOP Senator Jesse Helms ran in 1990. His Democratic challenger Harvey Gantt, the Black former Mayor of Charlotte, was running strong in the polls before Helms unveiled this ad, showing two white hands crumpling a letter as a narrator says: “You needed that job, and you were the best qualified. But they had to give it to a minority.”

The strategy didn’t always have to pit a Republican against a Democrat, either. George W. Bush benefited from it in his 2000 GOP primary campaign in South Carolina when there were strongly whispered rumors that John McCain had fathered an illegitimate Black daughter (she’d actually been adopted from an orphanage in Bangladesh).

More recently, you see the same thing happening in the birtherism issue that followed Barack Obama, or even this year when some Republicans denounced Kamala Harris’ nomination as a DEI hire. And while anti-immigrant sentiment has been around since the 19th century, it’s not much of a surprise that it’s Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, who are being demonized this year with a false story about crime.

This image from a recent Trump campaign tweet isn’t exactly subtle. “Import the third world. Become the third world,” it reads.

These sentiments are no different than the ones telegraphed by the Wallace campaign more than a half-century ago.

As for the Democrats, while they haven’t deliberately provoked racial anxieties, they have managed to exacerbate the debate at times by being overly moralistic or by pushing the envelope in ways that turned off Middle America. Political correctness, for instance, became a tool used for shaming and morphed into cancel culture. Terms such as white privilege, white fragility, white racist bias, and white oppression have more recently been introduced into the national discourse.

As Democratic strategist James Carville has noted, the motivations may be well intended, but some in his party “started using language that people do not use.” The result was that a growing number of voters, particularly whites in rural and working class communities, grew resentful over what they felt was lecturing or scolding from liberals.

And so the whole issue of civil rights was turned on its head, so that now there’s a concurrent discussion about anti-white discrimination in America. Trump has even taken up the cause, suggesting that “there is a definite anti-white feeling in this country.”

No matter what you believe, whether you’re coming at this from the left or the right, it’s not hard to see that this issue is damaging to democracy. Because when politics is about triggering anxieties or about seeing certain groups or political opponents as The Other, it just encases us deeper in our own tribal bubbles.

So, yes, even now in 2024 we’re dealing with the effects of an issue that was sparked when Blacks found success in their long struggle for civil rights, and when a segregationist Alabama governor in 1968 found traction in the presidential race by criticizing civil rights laws and the “liberal elitists” who implemented them.

Since then, one thing led to another, over and over again, and now here we are. Different words, same fight, for nearly six decades. And the impact on the political landscape has been enormous.