Let’s Talk About How We Pick Presidents (Part Two)

Why do voters choose presidential nominees, anyway?

In yesterday’s post, we looked at what the Constitution had to say about selecting presidential candidates (i.e., nothing) and at how the nominating process evolved in fits and starts for the first half-century of American life, culminating with the first national political conventions in 1832. There have been far fewer changes to the nominating process since then, but there have nevertheless been a few seminal events that dramatically changed how presidential candidates are selected.

So let’s take a look at three more key moments, which show how we went from party leaders and loyalists choosing candidates in the 19th century to today, when voters now have the greatest say in the process.

1. 1832 to 1908: National Political Party Conventions

For three-quarters of a century after 1832, the practice of selecting presidential candidates at a national convention remained pretty static. The idea was to bring together party leaders and loyalists from every state and to have this group vote for a nominee. In some years, it was a fairly cut and dried process, with one obvious candidate standing out above the rest. At other times, the vote was filled with drama. But decisions were always made by individuals who were actively involved in the party.

One of the more dramatic years for political conventions was 1860, when both parties made consequential decisions in a country that was on the brink of the Civil War.

At the Democratic convention, the most popular candidate was Illinois Senator Steven Douglas, known as the Little Giant because of his 5’4” height but outsized political stature. At the convention in Charleston, South Carolina, however, he wasn’t able to gain the necessary majority because of opposition from southerners who wanted him to accept a more proslavery platform.

When the slavery dispute caused scores of southerners to walk out, the convention adjourned. Eventually, at separate meetings, northern Democrats nominated Douglas and southern Democrats nominated Vice President John Breckenridge of Kentucky. Douglas and Breckenridge then both competed in the general election.

That same summer, when the Republican convention convened in Chicago, Senator William Seward of New York was the prohibitive favorite. But Seward faced pushback from party members who were afraid his reputation on slavery was too liberal to win a national election. So on the third ballot, delegates swung to a compromise candidate, former Illinois Congressman Abraham Lincoln.

The choice of Lincoln shocked the political establishment, as the Illinoisan was a well-known orator but had only served a single term in Congress a decade earlier and had most recently lost a Senate contest to Douglas. The same Senate race, by the way, that gave us the famed Lincoln-Douglas debates.

There were surprises in other years, as well, though perhaps none so consequential as in 1860. In any case, for 76 years after 1832 this is how the nation’s political parties chose their presidential nominees.

And then came 1912.

2. 1912 to 1968: Voters Get Involved (somewhat)

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a Progressive movement in American politics worked to open up democracy and get voters more involved in elections. U.S. Senators, for instance, used to be selected by state legislatures, but the 17th Amendment to the Constitution in 1913 gave voters the power to directly elect Senators. The same idea was introduced to presidential elections around this time, which is when the idea of holding presidential primaries was born.

The first primaries were held in 1912. Only 12 states held contests, but they chose quite a year to introduce this innovation. As it happened, former President Teddy Roosevelt was disenchanted with his Republican successor, William Howard Taft, and decided to run for another term by trying to wrest the nomination away from the incumbent. So, for the first time ever, the country saw presidential candidates compete for their party’s nomination.

Roosevelt had been out of office four years, but he was still the country’s most popular figure and he defeated Taft in 9 out of 12 primary contests. He won 278 delegates to 48 for Taft. Today, that performance would have given Roosevelt an overwhelming victory and he would have easily emerged as the party nominee.

In 1912, however, primaries only accounted for a portion of delegates to the convention and most votes were still controlled by state parties loyal to the sitting president. Once party leaders got involved, Taft won the nomination on the first ballot. This didn’t sit well with Roosevelt’s supporters and it fractured the Republican Party.

Another convention was organized, at which a new Progressive Party was founded (this happened, obviously, at a time when many progressives were Republicans). That fall, Roosevelt ran as the Progressive Party candidate. But he and Taft split the GOP vote, which helped Democrat Woodrow Wilson win the presidency.

Few elections ever again produced the drama of 1912, but the advent of primaries did produce a new hybrid system for nominating presidential candidates. For the next half-century, final decisions were still made at conventions — and nominees still required the support of key figures in the party — but some candidates ran in primaries to showcase their candidacies.

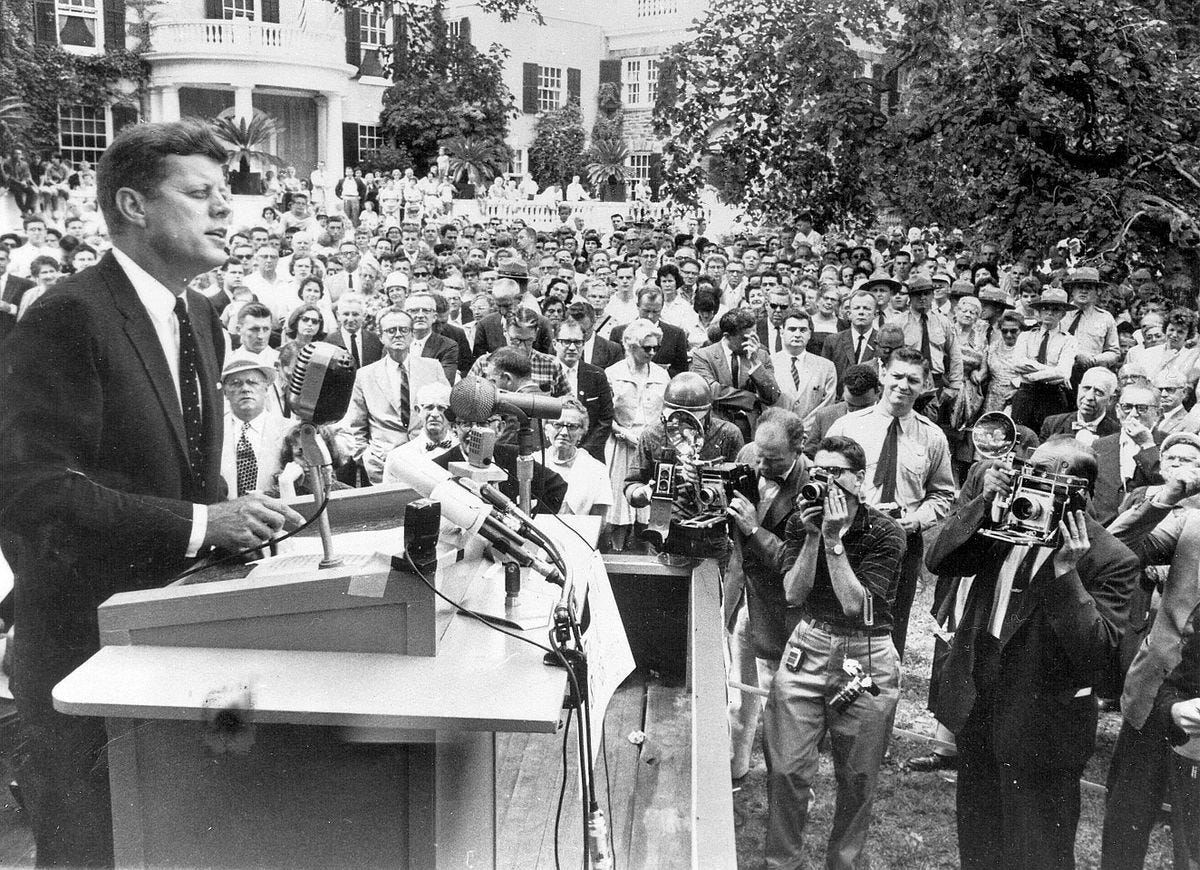

The best example of this might be from 1960, when 43-year-old Massachusetts Senator John Kennedy was seen by many Democrats as too young and too Catholic to be elected president. But Kennedy put together a campaign that defeated Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey in a few key primaries to prove his vote-getting ability. After knocking out Humphrey, he then rounded up enough support from party leaders to prevail over Texas Senator Lyndon Johnson in a floor fight at the convention.

3. 1968 to Today: Voters Take Over the Nominating Process

If it weren’t for 1968, the hybrid system of relying on primaries, combined with support from party leaders, might have continued for quite some time. Who knows, it might even still exist today.

But in 1968, after President Johnson chose not to run for re-election, two Democrats ran in party primaries: Senators Robert Kennedy of New York and Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota. Vice President Hubert Humphrey, meanwhile, skipped the primaries and opted to try winning the nomination solely with the support of party leaders (as LBJ had tried and failed to do in 1960).

Kennedy and McCarthy were both popular with antiwar voices in the party and each won some primaries, but RFK’s win in the vital California contest appeared to set him up as the main challenger to Humphrey at the convention. After Kennedy’s assassination, though, Humphrey went on to win the nomination over McCarthy, before losing the fall election to Richard Nixon.

In the aftermath, there was a movement to change the nominating rules so that a candidate like Humphrey could never again win a nomination without entering a single primary. So the Democrats instituted new rules to incentivize states to select delegates through primaries and caucuses.

In 1972, then, South Dakota Senator George McGovern assembled a grassroots movement that won him the Democratic nomination, even though he wasn’t the preferred candidate of party leaders. He was the first person to win a nomination entirely with support from voters instead of party leaders. Four years later, in 1976, Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter did the same thing and, along the way, put the Iowa caucuses on the presidential map. The GOP went along and also gave more power to voters in the nomination process.

Since McGovern and Carter, voters have mostly selected candidates who were (at least somewhat) acceptable to the party establishment. There have, however, been exceptions — such as Donald Trump’s win in the 2016 nomination battle, one he almost surely wouldn’t have won if party leaders had any say in the matter.

In any case, the 1972 reform that took power away from party leaders and turned it over to voters is the most recent significant change in the way presidential candidates are nominated. It’s notable that no other major democratic nation gives voters so much of a voice in choosing party nominees.

In the U.S., this voter-driven nominating system has made the process more democratic and it forces candidates to gain popular support, which has its advantages. But it also makes for longer campaigns, amplifies the voices of the loudest activists and richest donors, and takes away the power of the party to filter candidates. Now, populists who can amass a passionate following have more advantages in their efforts to win party nominations.

For better and for worse, this is the reality of presidential politics today. Whether it will remain so, only the future knows. Since the Constitution is silent on the whole concept of nominating presidential candidates, well, it’s up to the parties (and their supporters) to figure out where things go from here. If we’ve learned anything from history, it’s that nothing is static forever.

This essay was written for Substack, but parts of it were adapted from my book, Quest for the Presidency: The Storied and Surprising History of Presidential Campaigns in America (Lincoln, Nebraska: Potomac Books/University of Nebraska Press, 2022).

And please think about a free or paid subscription to The Riel World if you’re not already a subscriber.