Let's Talk About the Electoral College

Why do we have an Electoral College? And how might it impact the 2024 election?

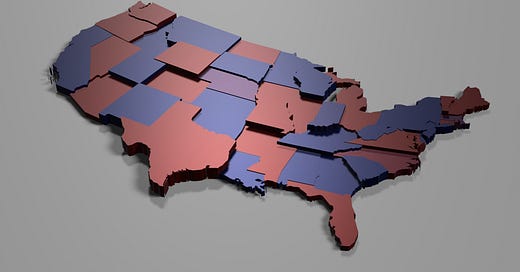

Are we headed for another popular-electoral vote split in 2024?

Next week’s presidential election is so close, according to polls, it’s a coin flip. Which means it’s possible the United States will see another result where one candidate wins the popular vote and the other prevails in the Electoral College.

As I write this, in fact, Nate Silver’s model gives Kamala Harris a 74.6% chance of winning the popular vote, and Donald Trump a 53.8% chance of coming out on top in the Electoral College.

There are seven swing states that are within about 1% in the polls, and the key one seems to be Pennsylvania. Whomever prevails there will have considerably better odds of winning. But the state is on a razor’s edge, with Trump currently up 0.6% in Silver’s polling model. Polls are never exactly right, and late-breaking voters may swing the result more decisively in one direction, but a split between the popular and electoral votes is certainly within the realm of possibility.

If so, it would be the second time in three elections, and the third time in seven cycles, that the loser of the popular vote won the White House. In all three instances, it would apparently be the Republican candidate who benefited from the split. (Though Nate Cohn in the New York Times recently raised what he said was an unlikely but not impossible scenario where Harris could win the electoral vote while losing the popular tally.)

The last time there was a split presidential decision twice in such a short period of time, in 1876 and 1888, each party won one national election. There wasn’t another division between the popular and electoral votes for 112 years after this, which lulled Americans into a false sense of believing this was a rare, random occurrence.

Close calls in the 20th century

In reality, though, there were actually a number of close calls in the last century.

In 1916, Woodrow Wilson was re-elected after winning California by just 3,773 votes out of one million ballots. Had California voted Republican, Charles Evans Hughes would have won the electoral vote 267-264 despite losing the popular vote 49–46%.

In 1948, Harry Truman defeated Thomas Dewey 49-45% in the popular vote. But in Ohio and California his margins were 7,000 and 17,000 votes. If Dewey won both states, no one have won a majority because the southern conservative Dixiecrats had won four states with 39 electoral votes. So a few thousand voters in two states was all that prevented the election from being thrown into Congress.

In 1960, John Kennedy edged Richard Nixon in the popular vote by just 49.7 - 49.6%. Essentially a tie. Nevertheless, he won Texas by 46,000 votes and Illinois by less than 9,000, and Nixon would have won the presidency by flipping those states.

1968 was similar to 1948. Nixon defeated Humphrey by 43.4 - 42.7%, with the independent George Wallace winning 13.5% of the vote and 46 electoral votes. If fewer than 78,000 ballots in Missouri and Illinois had flipped from Nixon to Humphrey, no candidate would have won the Electoral College and Congress would have had to choose the president.

And in 1976, Jimmy Carter won the popular vote 50-48%, but if 9,300 votes in Ohio and Hawaii had shifted from Carter to Gerald Ford, then Ford would have won re-election despite losing the popular vote.

That’s five close calls, including two times when Congress almost had to decide the winner. So it’s nearly a miracle the country wasn’t awash in many more controversies.

Given this, and given the current electoral map, one has to ask why the U.S. has an Electoral College system in the first place. Especially since it’s the only major democratic nation that elects its head of government in this way.

So, in the same spirit as my previous posts about why Americans nominate presidential candidates in the way they do, let’s try to answer the question of why we have an Electoral College.

How the Founders viewed the Electoral College

When a new Constitution was written in 1787, there was considerable debate over how to elect a president.

Delegates to the Constitutional Convention initially assumed a president would have to be chosen by Congress, but this idea was discarded because of fear the executive and legislative branches wouldn’t be independent from each other.

Another option was to have people elect the president directly. “[If the President] is to be the guardian of the people,” said Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, “let him be appointed by the people.” But there was minimal support for this because democracy was relatively untested on a large scale and most delegates wanted a buffer between the people and the election of a president. It also seemed impractical, as most voters weren’t informed about candidates from other states at a time when it took a week to travel just from Boston to New York by horse and carriage.

But if election by Congress and the people were both off the table, there weren’t too many other great ideas floating around for how to select a president. So, at the end of the Constitutional Convention, worn down by “fatigue and impatience,” as Madison noted, they forged a compromise. Each state legislature would choose a set of electors and this group would vote for a president.

There are two important points about why this solution made sense during that period of U.S. history.

First, there were no political parties then, so the assumption was that leading citizens from each state would make somewhat of an enlightened decision and would choose individuals who’d govern in the national interest.

Second, the thinking was that future candidates (other than George Washington) would only rarely gain a majority from these state electors. Thus, the electoral vote would mostly narrow the field to a few contenders and Congress would then make the final decision from among the top candidates.

In effect, the electors from each state were responsible for nominating candidates. If enough of them agreed on a top choice, well, that person would be elected; if not, Congress would take over the decision after the field had been whittled down.

So, yes, the Electoral College was initially more of a nominating system for presidential candidates!

Then came political parties … and a popular vote

The first factor that started transforming the electoral system designed by the Founders was the advent of political parties.

Absent a popular vote in presidential elections, each faction began lobbying state legislatures to appoint electors favorable to one political party or another. When Thomas Jefferson defeated John Adams in 1800, for instance, the election turned on a New York legislature that switched allegiance from Adams in 1796 to Jefferson in 1800.

The first five presidents were elected this way. A national popular vote wasn’t tallied until 1824, and even then not every state participated. Eventually, though, all states turned to a popular vote and began awarding electors to the winner of their state’s balloting.

So really, it’s more an accident of history that we have the system we do. What began as a way for states to nominate candidates for president evolved in a patchwork way over time into the system that exists today.

Democracy in the U.S. evolved, but the Electoral College didn’t

What’s interesting is that so much else about American democracy has changed in the past two plus centuries.

In the 1700s, only white male property owners could vote. Now, any U.S. citizen above 18 is eligible to cast a ballot (with some exceptions for those with criminal records).

U.S. Senators used to be selected by state legislatures. But the 17th Amendment in 1913 gave voters in each state the power to elect Senators.

Presidential candidates used to be selected by the leaders of political parties. But since 1972 they’ve been selected by voters through a series of party primaries and caucuses.

Even as democracy continues to expand, however, the Electoral College has remained stubbornly in place. There have been hundreds of calls to abolish or change the Electoral College through the years, but none have succeeded.

Southern states were one impediment to change for many years. Before the Civil War, three-fifths of slaves counted as part of a state’s population for census purposes, and after the war all Blacks counted; however, most Blacks there couldn’t vote until the 1960s. This meant the South had more representation in Congress (and by extension more electoral votes) than was merited based on its white voting population.

Today, there are small states that have more electoral power than they otherwise would based on population, and swing states that get inordinate amounts of attention from candidates and the media.

The latest group to resist change is the Republican party, as its support for eliminating the Electoral College dropped considerably after the 2000 and 2016 elections. Donald Trump himself declared in 2012 that the Electoral College was a “disaster for a democracy,” but changed his tune pretty quickly a few years later.

Of course, if Harris were to win this year while losing the popular vote, well, these opinions could flip again. On both sides of the aisle.

1969: When the U.S. nearly eliminated the Electoral College

There was one time, however, when the U.S. came within inches of actually abolishing the Electoral College in favor of a national popular vote.

After the 1968 election, Americans were alarmed at Wallace’s near success in blocking a victory by Nixon or Humphrey, particularly since Wallace’s main goal was to make himself a kingmaker in such a scenario. So a movement arose to replace the electoral system with a national vote. A constitutional amendment was written, giving the election to the popular vote winner (with a runoff scheduled if the leading candidate ever had less than 40% of the total vote).

The idea was endorsed by President Nixon and backed by 80% of the public. At least 30 states also indicated they were ready to pass such an amendment. In 1969, the legislation sailed through the House of Representatives by the overwhelming margin of 338-70.

However, the bill died in the Senate when it couldn’t overcome a filibuster by southern Senators who weren’t thrilled with the idea of putting Blacks on an equal footing with whites in one-person-one-vote elections. This was just a few years after the Voting Rights Act had given Blacks the right to vote in the South, so this change would have meant the white majority in those states would no longer be able to influence the electoral vote in the same way.

The U.S. has never again come close to replacing the Electoral College.

The Electoral College today

The electoral vote is controversial among a fair number of Americans today for a few reasons. High on that list is the fact that not all votes are created equal. After all, if you’re in Vermont or Idaho right now you might as well not exist for presidential candidates and your vote is less likely to affect the final result.

On the other hand, Pennsylvanians and Georgians are being lavished with candidate appearances and advertising money. The entire election will likely be decided by a few thousand people in those states and several others, and by some voters who don’t even pay much attention to politics.

Then, there’s the fact that the popular vote winner has actually lost two of the previous six elections. Notably, there is no evidence the Founders ever intended for a minority of the country to be able to elect a president. They were concerned with checks and balances (for ambition to counteract ambition, as Madison put it) but not for a minority to be able to rule over a majority.

Moreover, these split results of late have resulted from an Electoral College bias that has forced Democratic candidates to win the popular vote by at least two percentage points (and more likely by 3-4%) in order to also win the electoral tally. This is because the tipping point state in the electoral vote in recent elections has been more conservative than the popular vote across the entire nation.

Interestingly there is some data that indicates this bias might be shrinking … if this year’s polls are correct that Trump is gaining votes among Blacks and Latinos, for instance, while Harris is making equivalent gains among previously Republican suburban voters in states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin (if you’re really curious, more details here and here). But we won’t know until the election is over if anything has changed, or if a Democrat still needs to win the popular vote by 2-4% in order to prevail in the electoral vote.

There is, however, one movement afoot that could do away with the Electoral College without a constitutional amendment. The National Popular Vote Compact. Under this scenario, states would agree to assign their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote rather than to the winner of their state’s vote. It’s legal because the Constitution enables each state to determine rules for its own electors.

This compact has currently been enacted by 17 states with 209 electoral votes (with the provision that it only takes effect when states with a total of 270 votes have agreed). Not a single red state is among those 17, however. It’s been suggested that this compact is likely to be adopted only if a Democrat were to reverse the recent Electoral College trend and managed to win the presidency after losing the popular vote.

So, barring a surprise event or a dramatic turnaround, we’re likely to be dealing with this patchwork of an electoral system for many years to come.