What Could Donald Trump Learn from James Garfield's Presidency?

Perhaps why the government has career civil service employees

Donald Trump’s attack on career civil service employees

Donald Trump sure seems to be following through on his promise to blow up the federal government and eliminate or replace thousands of employees. Which, to a lot of voters, sounds like a splendid plan. Fire bureaucrats, get rid of the deep state, right? Then there is the argument that a president deserves to have loyalists installed throughout government, devoted to implementing his agenda.

In the abstract, the argument makes sense. But the truth is, the career civil service exists for a pretty good reason, one which James Garfield could tell us about if he were here today. Before we get to that, though, let’s review where things stand in early 2025.

Thus far, a little more than two weeks into his presidency, President Trump has removed leading officials at the FBI, Federal Aviation Administration, Transportation Security Administration, US Agency for International Development, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and Census Bureau, among others.

He has also fired 17 inspectors general, as well as members of the Aviation Security Advisory Committee, National Labor Relations Board, and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Trump has also issued an executive order, Schedule F, to enable him to reclassify tens of thousands of employees so that any of them could be fired without cause.

The alleged justification for these actions is a need to cut government and make it more effective. And if that is, in fact, the goal then, sure, there’s nothing wrong with downsizing if it means cutting wasteful spending and making things run more efficiently. Who could be opposed to that?

So far, however, this effort seems aimed more at retribution and ideological cleansing than at government efficiency. It’s more akin to the purges of the mid-20th century when supposed Communist sympathizers lost their jobs during the Red Scare, along with a range of other employees, including civil rights activists, anyone alleged to have engaged in homosexual activities, even foreign service agents who had worked in China.

To see that this isn’t really just about efficiency in government, all we have to do is look at who’s been relieved of their duties so far. In addition to everyone mentioned above, there have been widespread terminations of anyone who has ever been involved in any program related to diversity. Also, individuals who work on foreign aid and consumer protection issues. And soon, vast numbers of employees at the Education Department, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Centers for Disease Control and other public health agencies, who’ve all been put on notice that thousands of their jobs will be eliminated.

Not to mention that anyone who has angered Trump is out, even if they were just doing their job, such as dozens of FBI agents and lawyers who’ve been fired simply for working on January 6th prosecutions. The administration additionally seems to be readying a purge of thousands more FBI employees who were involved in these and other Trump-related investigations, which has caused FBI agents to sue their own government over the issue. And there is evidence that DOGE minions are sifting through all employees’ work and communication histories to look for any evidence of progressive thinking or disloyalty to Trump.

Considering all this, it’s hard to see the Trump-Musk DOGE initiative as a means of reforming government. It’s more akin to taking a sledgehammer to any program or person with whom they disagree or who is perceived as disloyal. In the end, this is meant mostly to reshape the government so that it’s loyal only to the president and/or the MAGA movement. Not to Congress, or the rule of law, or science, or the courts.

But the thing is, we’ve tried this before. In the 1800s. And it didn’t go so well.

James Garfield, in fact, might tell you to be careful what you wish for. That’s because Garfield’s election to the presidency in 1880, his assassination the following year, and the trauma experienced by his vice president in relation to these events, were all linked to a controversy over the role of civil servants in a government bureaucracy. And they hold lessons for us today, nearly a century and a half later.

The 1880 presidential election

When President Rutherford B. Hayes chose not to run for re-election in 1880, the presidential race was thrown wide open. The Democrats easily nominated General Winfield Scott Hancock, but the race for the Republican nomination was a heated one that lasted 36 ballots at that summer’s convention.

And the battle was fought, in considerable part, over the issue of government jobs.

At the time, a patronage system dominated American politics. The winners of national elections handed out tens of thousands of jobs to party supporters, a benefit known as the spoils system, after the phrase, “To the victor belong the spoils.”

But as historian Lindsay Chervinsky noted:

Party bosses granted these positions as rewards to loyal operatives and used them as cudgels to force supporters to toe the party line. Unsurprisingly, this system was wildly inefficient and bred widespread corruption because politicians selected officeholders for their political utility rather than merit.

Consequently, by the 1880s many were convinced that civil service jobs should be awarded not through patronage but via a merit-based system. President Hayes tried to enact civil service reform but only managed to anger leaders in his own party, especially when he replaced the Collector of the New York Customs House, a man named Chester Arthur. This infuriated New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, the leader of a group known as the Republican Stalwarts (because of their “stalwart” defense of party traditions, including patronage).

In 1880, the Stalwarts decided to endorse Ulysses Grant for an unprecedented third term as president. Grant had served two previous terms, then left office in 1877 and embarked on a two-year trip around the world. Back home now, he was still immensely popular and the Stalwarts saw Grant as a strong leader but one who wouldn’t interfere with the party’s patronage efforts.

Not all Republicans favored another term for Grant, however. This other faction was known as the Half-Breeds because they were said to be half-loyal to Grant but also half-loyal to the idea of reforming government, particularly in advancing the idea of a career civil service and replacing the spoils system. They preferred Senator James G. Blaine of Maine for the nomination.

At the Republican convention in Chicago that June, the Stalwarts and Half-Breeds battled through dozens of ballots with neither Grant nor Blaine securing majority support. On the 34th ballot, in an effort to break the deadlock, the Wisconsin delegation surprised everyone by shifting 16 votes to Ohio Representative James Garfield.

Garfield was a nine-term House member and a Major General during the Civil War, so he was a plausible president. But Garfield wasn’t angling for the job and protested that he hadn’t given consent for his name to be put forth as a nominee. It didn’t matter. His vote total soon grew, as delegates saw a way out of their deadlock. Blaine then freed his delegates to support Garfield if it would block the Stalwarts from winning.

On the 36th ballot, a stunned Garfield won the nomination. “Won’t you telegraph my wife?” Garfield asked a friend. “She ought to know of this.”

To soothe hurt feelings and unify the party, the convention agreed to nominate the Stalwarts’ pick for vice president. After their first choice rejected the opportunity, the Stalwarts surprisingly turned to Chester Arthur, the man who’d been ousted as Collector of the New York Customs House, even though he had no other experience in national politics.

After this, the general election battle between Garfield and Hancock was one of the closest in history. Of more than 9 million votes cast, less than 10,000 separated the candidates, with Garfield winning 48.3-48.2%. The Electoral College margin was a bit wider, with Garfield prevailing 214-155.

Garfield’s assassination

Then, less than four months into his presidency, President Garfield was shot by an assassin. And the shooting was linked, astonishingly, to the drama between Stalwarts and Half-Breeds that marked the Republican convention the previous summer.

You see, during Garfield’s first months in office, he was engaged in tremendous disagreements with other party officials over patronage jobs. Many of the battles were with the Stalwart leader, Senator Conkling. As it happened, Vice President Arthur supported Conkling and his old Stalwart colleagues over the president, a choice that would soon haunt him.

On July 2, 1881, Garfield was shot while walking through the Baltimore and Potomac railway station in Washington. The assassin, Charles Guiteau, was a seemingly unstable man acting on his own, but he was also a Stalwart supporter who believed he himself had been unfairly passed over for a job. After the shooting, Guiteau declared: “I am a Stalwart and Arthur will be president.”

The news rocked the nation. People had always assumed that Lincoln’s assassination was an outlier, a tragic consequence of the Civil War. But now another president had been shot, this time because of a dispute over who should get which patronage jobs.

By coincidence, Arthur and Conkling were together in New York when the shooting happened. As people realized the attack was motivated by anger over the spoils system and was an effort to install Arthur in the presidency, fingers were pointed accusingly at the two men, who received death threats.

Garfield survived the initial shooting and was moved to the White House, where he lingered in serious condition for the rest of the summer. He was eventually moved to a seaside home near Long Branch, New Jersey, in hopes the ocean air would revive him. But he died there on September 19.

Soon thereafter, a messenger appeared at Arthur’s door in New York City, informing him of Garfield’s death. The vice president broke down sobbing. He’d never aspired to the presidency and had spent the past few months in a stupor, distraught over reports of the Stalwarts’ unintended complicity in the assassination. Now Garfield was gone, and Arthur was the 21st president.

The rise of a civil service

Garfield’s death initially seemed to have achieved his assassin’s goal of preventing civil service reform, since Arthur was a Stalwart who owed his career to patronage. But to the surprise of many, the assassination spurred President Arthur to a change of heart and gave new impetus to the reform movement.

In 1883, Arthur signed into law the Pendleton Act, which created a Civil Service Commission and ensured that federal workers would thereafter be hired on merit rather than by their ties to a politician. It also made it illegal to fire any employee for political reasons.

This civil service, of course, grew into the federal bureaucracy that so many people bemoan these days. The upside is that it ended a system that treated elections as patronage contests, when political bosses were in control of most federal jobs. The reforms helped to professionalize government and reduce the potential for corruption.

Today, the civil service encompasses FBI agents, weather service forecasters who predict hurricanes, food inspectors who try to prevent outbreaks of food-borne diseases, border patrol agents, education officials who disperse financial aid for college students, cancer researchers at the National Institute for Health, air traffic controllers, doctors and nurses who provide health care for veterans through the VA, and much more.

But now, almost 150 years after the drama of the 1880s, there is a movement to eviscerate the civil service and bring back some form of the spoils system. This would give thousands of federal jobs, including vital positions managing various departments, to political supporters of an incoming president rather than to career officials who have spent their lives accumulating expertise in particular areas of government.

It’s pretty common for people and countries to lose historical memory after a few decades, never mind more than a century. Still, it may not be such a bad thing to reflect on the late 1800s, and particularly the presidencies of Garfield and Arthur, when contemplating such a sweeping change as gutting the civil service.

This essay was written for Substack, but parts of it were adapted from my book, Quest for the Presidency: The Storied and Surprising History of Presidential Campaigns in America (Lincoln, Nebraska: Potomac Books/University of Nebraska Press, 2022).

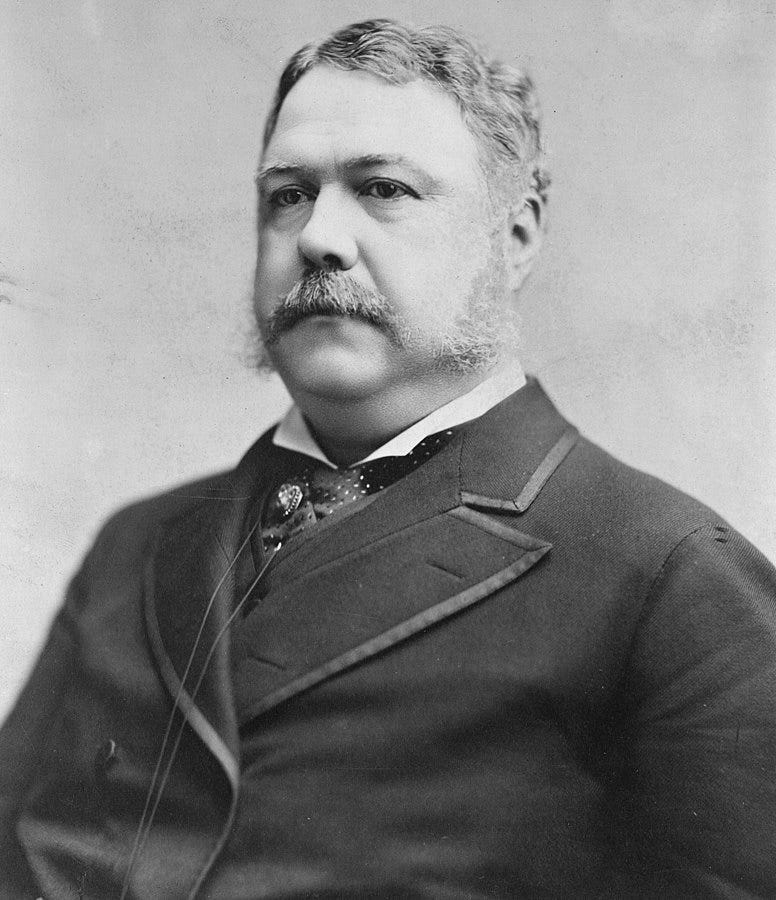

Images: Public domain images from Wikimedia Commons of James Garfield, Donald Trump, Chester Arthur, and an engraving of the Garfield assassination.