Three Years that Broke American Politics (Part Two)

1994: The politics of obstruction and anger, plus profound changes in the American media

Three years the broke American politics. Part Two: 1994. The introduction to this series can be found in Part One: 1968.

The quick 1994 backstory

1994 wasn’t a presidential election year, but a midterm contest. Yet the election was consequential in ways that still influence politics in the United States.

Two years earlier, in 1992, Bill Clinton won the presidency. He took office amid high hopes, but the Clinton presidency was dogged by turmoil. A series of controversies and scandals played a significant role in this and can’t be dismissed. But the tumult was also linked, we can see in retrospect, to two developments that were just beginning to transform the U.S. political environment.

One was the shifting world of news, marked first by CNN and the advent of a 24-hour news cycle, and later by an emerging right-wing media. The other factor was a more antagonistic approach to politics preached by Georgia Congressman Newt Gingrich.

1994: Newt Gingrich and the politics of obstruction and anger

When Gingrich entered Congress in 1979, he brought a theory of politics as warfare in which the only way to triumph was to be vicious. As he told one audience: “One of the great problems we have in the Republican Party is that we don’t encourage you to be nasty.”

In Washington, Gingrich attacked his opponents in ways that went against the norms of the time and disrupted what was then a more civil way of doing legislative business. By the time Clinton became president, Gingrich was the GOP Minority Whip and convinced his party to oppose most every Democratic proposal, even those that had bipartisan support, as a way to deliberately obstruct Congressional legislation.

This was considered a drastic idea at the time, including by some in his own party. It was also an audacious bet on the belief that voters wouldn’t notice GOP obstructionism and would instead blame the Clinton Democrats for a lack of progress.

Additionally, Gingrich worked to change the language of politics. In order to paint Democrats as outside the mainstream of American life, he circulated a list of suggested words for colleagues to use when talking about opponents. Words such as anti-family, anti-flag, pathetic, bizarre, radical, sick, corrupt and traitors.

The political scientist Norm Ornstein said Gingrich’s goal was to make voters “so disgusted by Washington and the way it was operating that they would throw the ins out and bring the outs in.” But since Washington wasn’t polarized then like it is now, numerous observers thought the strategy would never work.

Except that it did.

Voters who were frustrated by goings-on in Washington responded by punishing the president’s party, as Gingrich had predicted. Republicans won an historic landslide in the 1994 mid-terms, with a 54-seat swing in the House giving them control for the first time in 40 years. The party also won the Senate. Gingrich became Speaker of the House. So complete was the victory that some journalists suggested Clinton would never recover and would be a one-term president.

Why this is still important today

The tactics Gingrich introduced would transform America’s political landscape.

The next time a Democrat was elected in 2008 the GOP used the same Gingrich strategy to stymie initiatives proposed by Barack Obama, even bipartisan ideas. During the Biden presidency this is also what killed a two-party push to reform immigration. The goal was always to defeat bills that might be popular and then blame the governing party for the failure.

In the theory of politics as articulated by Gingrich, legislating is less important than messaging. Because if you negotiate with your opponent and a bill passes, the party in power gets credit; but if you obstruct and nothing gets done, the party in power gets blamed.

The downside, of course, is that, well, nothing gets done!

Not only did this strategy of deliberate obstructionism take hold, but so did the language Gingrich encouraged as a way to demonize the opposition.

Listen to Donald Trump, for instance, in one of many similar statements he’s made about Democrats: “We pledge to you that we will root out the communists, Marxists, fascists and the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.”

Thugs and vermin. And recently he said it might be necessary to use the military for election security to deal with “the enemy from within...We have some very bad people, some sick people, radical left lunatics.”

These words have little utility aside from vilifying political opponents as an Other. And it’s not confined to Trump. From members of Congress to conservative commentators, there are countless examples of such statements, which are identical to the tactics promoted by Gingrich. He intuited back then what studies have since shown, which is that anger is a great motivator in politics.

Now, three decades after 1994, these strategies are ingrained in our politics. McKay Coppins wrote in a profile of Gingrich in The Atlantic: “The great irony of Gingrich’s rise and reign is that, in the end, he did fundamentally transform America—just not in the ways he’d hoped. He thought he was enshrining a new era of conservative government. In fact, he was enshrining an attitude—angry, combative, tribal—that would infect politics for decades to come.

1994: Profound changes in the American media

The 1980s and 1990s were marked by momentous changes in American media. There were two new dynamics, in particular, that impacted the country’s political culture leading up to the 1994 election. And a third one that came a few years later.

1. The advent of the 24-hours news cycle.

Americans used to survive quite well without paying attention to the news 24 hours a day. Prior to the 1980s, most Americans found out what was happening in the world by reading the daily newspaper and then turning on, say, the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite, who was long known as the most trusted man in America.

Then, in 1980, along came CNN with a vision for a 24-hour news station, which changed how Americans consumed news. When there was a major event, viewers could tune in at any time of day to see the latest developments.

But there was an unintended consequence to this unfettered access to news: Which is, what does the media do when there isn’t a major event to report on but there are still 24 hours of programs that need content? In the absence of headline news, it turns out, reporters still have to find tantalizing stories to keep feeding the ratings beast.

In this environment, it’s not a surprise that 1987 and 1992 were when journalistic feeding frenzies first erupted over sex scandals in the Gary Hart and Bill Clinton presidential campaigns. Or that when Clinton controversies erupted in 1993, topics that might have merited only passing interest on Cronkite’s evening news (ever heard of Nannygate or Travelgate?) were now being amplified every hour on story-starved cable news broadcasts. The media has always been interested in controversy, but the appetite increased exponentially when there were hours of broadcasts to fill.

Gingrich realized all of this early on, which is why in the years leading up to 1994 he advocated for a more aggressive form of politics. “The No. 1 fact about the news media is they love fights,” said Gingrich at the time. “You have to give them confrontations. When you give them confrontations, you get attention.”

2. The emergence of conservative talk radio.

This era also saw the rise of a new right-wing media, which initially centered on conservative talk radio.

It’s hard to believe now, but prior to 1988 few radio stations aired political talk shows. This was largely because they were required to provide balanced coverage and refrain from airing ideas that favored one political viewpoint. This was known as the Fairness Doctrine, a regulation that dated to 1949.

But in 1987 the FCC under the Reagan administration repealed the Fairness Doctrine, arguing that it infringed on the free speech rights of broadcasters and that content should be determined by the free market and not be restricted by government.

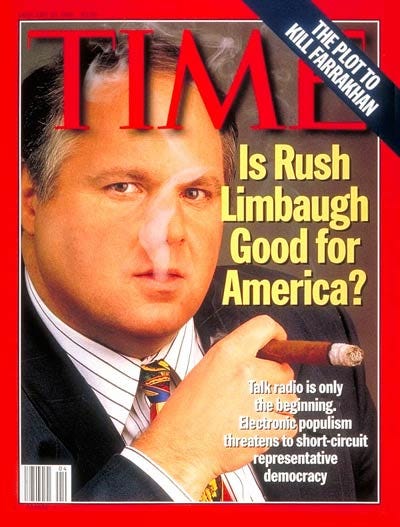

One year after the rule’s repeal, Rush Limbaugh launched a national radio show that revolutionized broadcasting and politics. Within six years the number of talk radio stations grew to more than 1,100, most of them conservative. Limbaugh himself had 20 million listeners on more than 600 stations.

One of the enduring mysteries of talk radio is why it became so popular with conservatives but not liberals. Various theories have been suggested, from the market-based to the psychological (i.e., one example is that liberals seem more entertained by satire and irony, which is the province of late night comedy, not talk radio).

Regardless of the reason, in just a few years talk radio became a cultural force that shaped and even dominated the political discourse.

Talk radio hosts were able to mimic cable news and amplify a story by repeating it endlessly. But these hosts weren’t journalists and had no obligation to keep opinions out of stories, so they could spin the narrative in any way they wished as long as listeners were entertained.

“What Rush realizes, and what a lot of listeners don’t,” an Atlanta station manager said, “is that talk-radio programming is entertainment, it is not journalism.”

And Limbaugh was the most provocative entertainer of them all, railing in the early 1990s against “commie-libs,” “feminazis” and “environmentalist wackos.” In 1993, five years after launching his show, Limbaugh was on the cover of Time magazine. His impact on politics was so influential he made the cover again in 1995.

In between those cover appearances, a poll of voters during the 1994 midterms showed that people who listened to talk radio for 10 or more hours each week were overwhelmingly likely to vote Republican. Those voters were credited with fueling the Republican wave of 1994.

3. The rise of Fox News and conservative television

In 1996, two years after the 1994 election, the Fox News network was born. This was in many ways an obvious next step in this new media culture.

Fox was a 24-hour cable station like CNN. And, like talk radio, it was a purveyor of conservative opinions. So Fox combined elements of what made CNN and talk radio successful. Fox and talk radio even aired many of the same stories, thus echoing and reinforcing each other.

Interestingly, MSNBC also launched in 1996. It was initially a partnership between NBC and Microsoft, a news channel that merged television with the internet. When ratings didn’t follow, though, it turned in a more progressive direction a decade later. Even so, it has never achieved the same popularity as Fox, which has been the country’s most watched cable news channel since 2002.

Why this is still important today

The existence of a partisan media isn’t unusual in U.S. history. In the 19th century, many newspapers were aligned with a political party. But eventually the media turned to a more objective form of journalism in which fact-checking and ethics became the norm.

While this is still the world in which the mainstream media lives, somewhere along the way it became fashionable on the right to criticize the press for bias. But is it true?

Actually, there are two answers here. First, no the the press isn’t actually biased. The media cares more about chasing a story than promoting an ideology. If this weren’t the case, would they really have so intensively covered, for example, the Clinton scandals of the 1990s, the Hillary Clinton email story of 2016, or the Joe Biden aging story of 2024?

But the other answer is, well, perhaps the press is biased in a different way. That is, in the way questions are framed or in some of the stories it chooses to cover. Conservatives made this argument decades ago, saying they felt left out of the national conversation.

From this perspective the emergence of conservative media outlets seems like it would be a good thing for democracy. Who could argue against journalists doing objective reporting, but with a conservative slant on stories and questions? More viewpoints are always better for democracy.

But that’s not exactly how it turned out.

While Fox has had flashes of objectivity in its reporting over the years, for the most part Fox and talk radio have focused more on conservative opinion than conservative journalism. And these opinions were often tinged with anger and grievance. One could argue that Fox, talk radio, and the Gingrich-style politics of anger were somehow all fused together in support of the same message, that Democrats are the enemy and are out to destroy the America you care about.

Was this intentional, or was it a business model that produced ratings and profits and was then impossible to stop once the ball got rolling? I don’t know, but what’s clear is that, just as with CNN’s 24-hour news, it produced an audience that needed to be fed. The anger had to be continually inflamed to keep ratings high.

This eventually caught up with Fox, at least to an extent. The network’s untruthful reporting on the 2020 presidential contest was so egregious that it chose to settle a defamation lawsuit with Dominion Voting Systems for $787 million to avoid a court trial that would have exposed how the station misled voters about the fairness of the election. As part of the same settlement, Fox agreed to fire its popular host, Tucker Carlson.

Fox itself, however, barely mentioned the settlement on air, so many of its viewers still don’t know about the falsehoods they were being fed.

Red vs. Blue America

The combined effect of all of this on America’s political culture has been dramatic.

In the 1960s, about 70% of Americans trusted news organizations to be fair. Today, that number still holds only among Democrats, with just 14% of Republicans now saying they trust the media. The two parties used to be closely aligned on the question, but the gap widened after 2000 and became a chasm during the Trump presidency.

Moreover, the conservative media propagated the belief that theirs was the only truth and anything reported elsewhere was either biased or a lie. This message worked, as 40% of Republicans who watch television news now say they only trust Fox to provide the truth. So, for a fair number of voters who identify as Republicans, a statement can only be believed if it comes from the GOP, talk radio, or a conservative news program. Everything else is suspect.

And it’s not just the media that is no longer trusted. Many people have also lost faith in science, government, and even elections. A Gallup poll this month shows that only 28% of Republicans believe in the accuracy of election results.

This all leads to the unfortunate loss of a shared reality among Americans. When two groups of people literally don’t believe the same set of facts, well, good luck in accomplishing anything as a country.

It’s obviously not the case that Americans have always worked together in harmony. U.S. history is rife with stark and bitter divisions. But the loss of a shared reality, and the vilification of opponents as enemies and traitors, is still something that really only happened during the Civil War era.

So it’s not a coincidence that the 1990s is also when the idea of blue states for Democrats and red states for Republicans first took hold. During the Bush versus Gore clash of 2000, talk of a red-blue divide resonated with Americans because of how the country’s political culture had been split open during the previous decade. The divisions, sad to say, have only deepened since then.

For further reflection on the differences between irony/satire vs outrage, I recommend this Hidden Brain podcast (this topic is about 3/4 through the episode): https://hiddenbrain.org/podcast/sitting-with-uncertainty/