The Politics of "Wicked" and the Wizard

How the story intersects with history and current events

The Academy Awards are airing on Sunday night (7 p.m. EST on ABC; Conan O’Brien is hosting). As one of the biggest hits of 2024, Wicked is up for numerous honors, including as one of 10 nominees for Best Picture. The movie is seen as a long shot contender to win the Best Picture award, but nevertheless … for purposes of this blog Wicked is actually one of the more interesting movies of the past year for how it intersects with contemporary discussions of politics and history. Hey, maybe that should be a category!

It’s admittedly an unusual movie to overlap with politics, as on the surface it’s mostly a story about a friendship between Glinda and Elphaba, two young women who meet as college students and who are fated to eventually become the Good and Wicked Witches in the land of Oz.

As Elle magazine noted: “Who would have thought the film of the year would be a rather intense political allegory disguised as a bubblegum musical?”

That said, there’s no doubt that parts of the movie struck a nerve with audiences — and even more so among those who also read the book on which it’s based. With the Oscar ceremony about to air, there’s no better time to break down what it is about Wicked that has people thinking about politics.

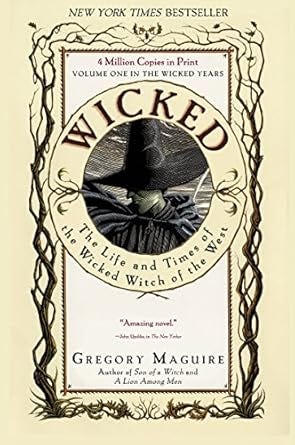

I saw the movie a few months ago and it inspired me to then read the novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West. I was particularly intrigued by the story in part because I’ve previously written about how the original Wizard of Oz book also overlapped with the history of its own time.

If you missed that earlier post, it might help to go back and read it here. But suffice to say that the Wizard of Oz, published in 1900, is thought by many to be an allegory of the politics of the 1890s. It’s symbolically representative of a rousing debate that was taking place in America at the time over the fairness of the gold standard and about an economy that was crushing farmers and factory workers. (Again, see my earlier post for a fuller explanation.)

So if the Wizard of Oz might be about the politics of the 1890s, could Wicked then be about the politics of the 2020s? Yes, but in a roundabout way.

The Wicked backstory

Wicked provides an imagined backstory for the Wizard of Oz and for the characters of Elphaba and Glinda. The novel was written by Gregory Maguire and was initially published in 1995. Assuming you’re familiar with the story, you know that Elphaba (whose name, incidentally, comes from the initials of L. Frank Baum, the author of the original Wizard of Oz book) was born with green skin into a humble family with a father who was an itinerant minister.

Elphaba is ostracized for much of her life because of her skin color. While attending Shiz University, though, she strikes up an unlikely friendship with her accidental roommate Glinda, who happened to have been born into a more privileged family and is at first aghast over the prospect of rooming with the green-skinned curiosity that is Elphaba. Over time, though, their connection grows into a friendship.

Elphaba’s personal experiences with ostracism give her a sense of social justice, which is why she takes to political activism when she discovers that the Animals (conscious animals who can speak, some of whom even work as college professors) are being oppressed. Her activism really takes off when she appeals to the Wizard for help, only to discover that it’s the Wizard himself who is behind the anti-Animal campaign.

This is when the story really turns political, though this is even more the case with the novel. In the movie, the politics is certainly there but it plays second fiddle to the story of the relationship between Elphaba and Glinda. In the book, these themes are reversed, with the politics taking precedence.

The politics of Wicked

In Oz, you see, a drought has helped to tank the economy. Citizens are getting restless and the Wizard realizes he must do something to soothe the populace. His solution? Scapegoat the Animals and make people believe they’re the source of everyone’s troubles. As Doctor Dillamond, a Goat professor at Shiz, explains: “Food grew scarce, people grew hungrier and angrier. And the question became: ‘Whom can we blame?’ " The Wizard decided to attack Animal rights, fire them from their jobs, remove them from society, and silence them by taking away their right to protest.

In a line that elicits one of the biggest responses from moviegoers, the Wizard defends his actions by declaring: “Where I come from, everyone knows: The best way to bring everyone together is to give them a really good enemy.”

Meanwhile, since the people of Oz have become conditioned to believe that Animals are to blame for society’s ills, few of them rise up to complain. So the Wizard — a second-rate leader whose biggest talent is an ability to provoke fear, manipulate opinion, and keep people divided — consolidates his power. He becomes an authoritarian leader and the land of Oz tumbles unwittingly into fascism.

Elphaba, though, refuses to stand idly by in the face of injustice. Instead, she tries to fight the regime. One thing leads to another and she eventually becomes demonized as the Wicked Witch. This is another example of how individuals (or groups) can become identified by a label that doesn’t necessarily relate to their original intentions. Misinformation can be more powerful than reality. Elphaba’s experiences in this sense are foreshadowed by Glinda’s line early in the movie when, in announcing the death of the Wicked Witch, she muses with a sigh: “Are people really born wicked, or is wickedness thrust upon them?”

How Wicked overlaps with American politics today

As to how the story of Wicked relates to America today, well, there are two things in particular that I think we can take from it, one potentially hopeful, the other one not so much.

1. Hopeful: It’s possible for people with different viewpoints to come to an understanding

The hope comes from the message that life isn’t binary, or black and white; there are a lot of gray areas and ambiguities. And instead of putting people and groups in boxes, we tend to be better off acknowledging that we all exist on a spectrum. Glinda and Elphaba fight through these tendencies to come to a new understanding of each other.

As another writer, Annie Reneau, put it in a piece for Upworthy:

“The point of Wicked is that good vs. evil narratives are overly simplistic. … Ultimately, the show implores us to question what we believe about others and recognize how easy it is to be influenced by propaganda and fear-mongering. … If we refuse to try to acknowledge that we might not be as right as we think we are and others might not be as wrong as we think they are, we might as well just be flying monkeys.”

The film’s director, Jon Chu, has similarly suggested:

“(Perhaps) the only way to actually find peace between us is maybe yell at each other, maybe say the things that we need to say, and actually forgive each other and give some grace, because the only way out is through.”

Forgive each other and give some grace across the political aisle? Sounds an awful lot like the “better angels of our nature” from Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural, doesn’t it?

2. Not hopeful: The similarities between U.S. politics today and past autocratic movements

Consider what I noted about the Wizard’s hold on Oz. That he was adept at scapegoating vulnerable groups of people and turning them into an enemy. Further, he was “a second-rate leader whose only real talent is his ability to provoke fear, manipulate opinion, and keep people divided.”

If you’re not a fan of Donald Trump, you might think that description hits a little close to home. And you might be disconcerted to see that the Wizard turned into an autocrat who ran a fascist-like state in Oz.

I know, I know, it’s a novel, not reality. Also, Wicked was obviously not written about the contemporary United States since it was published 30 years ago.

But here’s the thing: The novel was written by an author who undertook a study of fascist governments and then put together a story that focused in part on how authoritarianism arises. So any resemblance one might see between U.S. politics today and the fictional land of Oz, well, it’s not because the author intended for it to be about America. Rather, it’s because the U.S. today is sliding down a similar path to past autocracies, whether fictional ones like in Oz or real-life ones in Hungary, Turkey, or Russia.

David Crow explained it this way:

Rather than make Wicked like America circa 2024, America circa 2024 has made itself like Wicked.

Something to think about, at least, if you’re tuning into the Academy Awards tonight.

Bob, you’ve done it again. You took something I know (Kansas kid that I am) and brought a whole new meaning to it. I’m pondering…which is a good thing.

L Frank Baum was also a racist, calling for the “total annihilation” of “redskins” during the Ghost Dance uprising of 1890. “Why not annihilation? Their glory has fled, their spirit broken, their manhood effaced; better that they should die than live as the miserable wretches they are” Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, 12/20/1890