An Electoral College deadlock and talk of Civil War

No, not 2024 ... the election of 1800 (but even crazier than what you saw in "Hamilton")

From 1800 to 2024?

I have already written about the very real possibility that voters in Omaha, Nebraska, could cast the deciding vote in this year’s presidential election. Quite, simply, if the Democratic presidential candidate wins Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, while the Republican wins Arizona, Nevada, and Georgia (and all else stays the same from 2020), then the vote of the Congressional district centered on Omaha becomes crucial. Go with the Democrats and Joe Biden (if he’s still the candidate) wins 270-268; go with the Republicans and the election would finish in an historic 269-269 tie, with the president chosen by the House of Representatives.

If the House is tasked with electing a president, then according to the Constitution each state receives just one vote. Wyoming, with 581,000 residents, would have exactly as much power as California and Texas, each with more than 30 million people. Since it’s almost certain that Republicans in 2025 will control a majority of state delegations in the House, it’s quite likely that Donald Trump would win in that scenario (even if he lost the popular vote and even if Democrats had won back control of the House). So, depending on how things go on election day, it’s certainly not hard to imagine a contest that slides into weeks or months of controversy and outrage.

There is only one other time in American history that a presidential election ended in a tied electoral vote that had to be decided by Congress. That would be the election of 1800, which was featured in the musical “Hamilton.”

Lin-Manuel Miranda deserves all the accolades he received for that show, which debuted on Broadway in 2015, and for his brilliant retelling of the story of Alexander Hamilton and of America’s founding. However, because complex topics don’t easily translate to four-minute musical numbers, Miranda did have to leave out some history along the way.

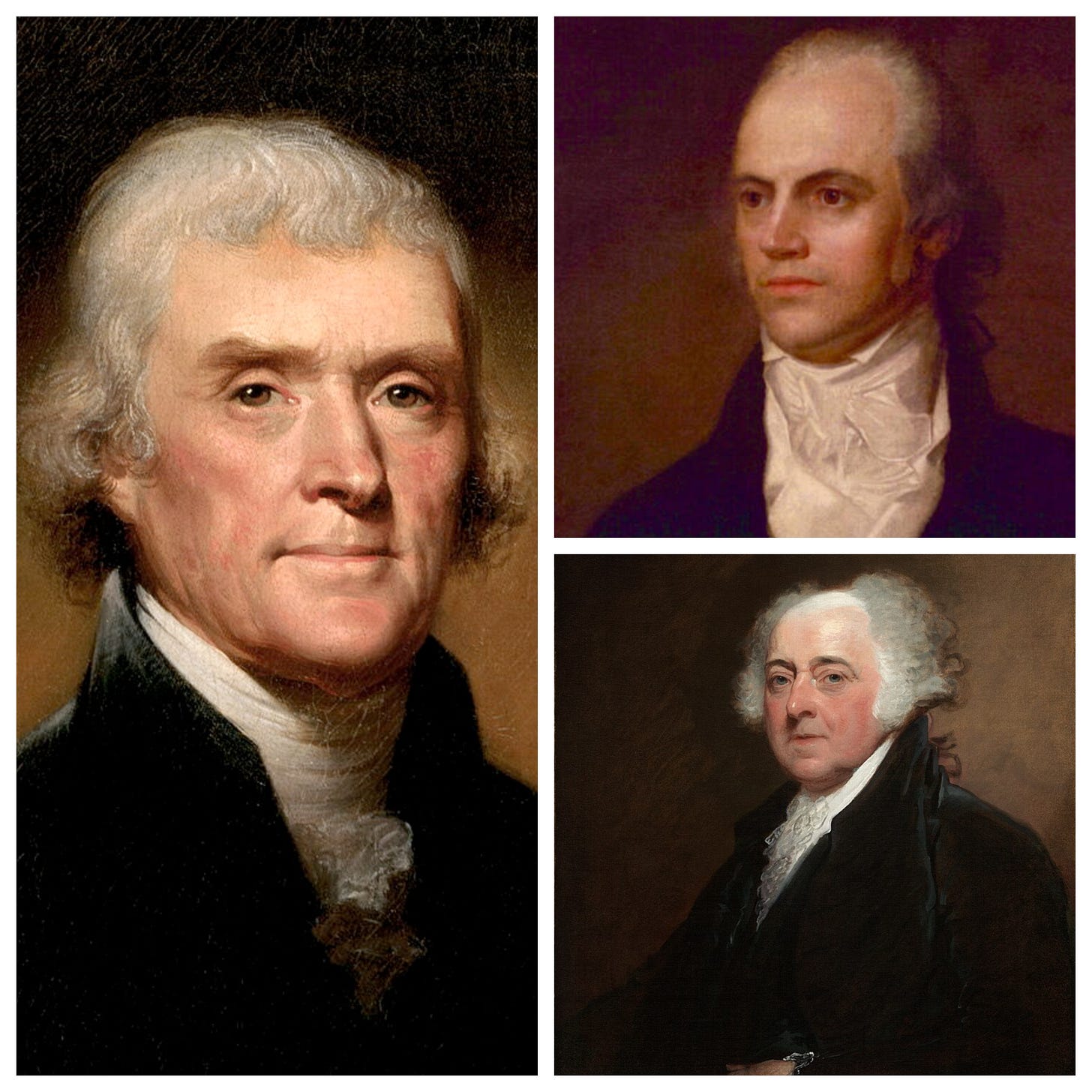

The Election of 1800 song, for instance, implies that Hamilton was the deciding vote in a tied presidential election between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr (later leading to a feud that ended with Burr killing Hamilton in a duel). The lyrics may be true enough in spirit, but they skim over some important details.

So, if all you know about the election of 1800 is what you learned in “Hamilton,” well, the reality was even crazier.

Here’s the rest of the story

First of all, Jefferson wasn’t running for president that year against Burr, but rather against the incumbent president, John Adams. Burr was actually the vice-presidential candidate on Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican ticket.

But if Burr was Jefferson’s vice-presidential candidate, then how did the two of them end up tied in the electoral vote for president?

Good question. One that shows the Founders were not, in fact, infallible. They actually wrote a Constitution with a pretty big glitch in it.

In 1800, the Constitution still called for electors to cast two votes for president, with the winner becoming president and the runner-up vice president. That’s because, when the Constitution was written in 1787, the Founders didn’t envision the advent of political parties. Rather, they believed that electors from each state would vote in a nonpartisan manner for an individual who was best qualified to lead the nation. There was also no provision at the time for a popular vote in presidential elections (and there wouldn’t be until 1824).

Thus, when the votes of electors were counted in 1800, Jefferson defeated Adams, of the Federalist Party, by a 73–65 vote. However, since all of the Democratic-Republican electors cast their two ballots for both Jefferson and Burr, it meant the running mates finished in a 73–73 tie. One of the Democratic-Republican electors was supposed to waste one of their second votes on a different candidate to ensure Burr finished behind Jefferson in the voting. But apparently no one got the memo.

And then things really went haywire

Everyone knew that Jefferson was the intended presidential candidate, but there was no way to constitutionally elect him after this tie — except through a vote in the House of Representatives, where (as noted) each state is allotted just one ballot. This gave the opposition Federalists another opportunity to try denying Jefferson the presidency.

The Federalists hatched a plan to try electing Burr instead of Jefferson in the hopes that Burr would be less ideological and perhaps more in their debt. Burr never campaigned openly for the job, but neither did he decline interest in the possibility, which encouraged the Federalists to push forward.

There were 16 states at the time, so Jefferson needed support from nine of them to prevail in the House. As fate would have it, there were only eight states with a Democratic-Republican majority. Six others supported the Federalists and two states were unable to cast a vote because their delegation was evenly split between the two parties.

Through 35 ballots over one week, Jefferson was unable to garner that elusive final vote to put him over the top. The deadlock appeared intractable and some states talked about the possibility of civil war if the showdown over Jefferson’s election couldn’t be resolved.

This is where Hamilton came in

Although Hamilton was a Federalist and was Jefferson’s bitter ideological rival, he considered Burr as lacking sufficient character to be president. Hamilton also worried about the impact on the nation should Jefferson be prevented from taking office after an election that he clearly won.

“If there be a man in the world I ought to hate, it is Jefferson,” Hamilton wrote. “But the public good must be paramount to every private consideration.”

(Hmm, “the public good must be paramount to every private consideration.” I know, where are the Hamiltons of 2024, right?)

In any case, Hamilton worked behind the scenes to convince Federalists to allow Jefferson to take office as the rightful winner. But since Hamilton had no actual vote in Congress it was left to James Bayard, Delaware’s lone Congressman, to break the standoff on the 36th ballot. After saying he’d received assurances that Jefferson wouldn’t entirely dismantle Federalist policies, he and others agreed to abstain from voting, which enabled Jefferson to gain the votes he needed to win the election.

Even after this controversy, it was nearly another four years before the Burr-Hamilton duel. Burr served a full term as Jefferson’s vice president, though relations between the two were strained. Then in 1804, knowing he was being replaced as Jefferson’s running mate for the next election, Burr decided to run for governor of New York. He was again opposed by Hamilton, and again lost.

It was after complaining about Hamilton’s slights of him during this gubernatorial campaign that Burr finally challenged Hamilton to that fateful duel, which took place on July 11, 1804.

This essay was written for Substack, but parts of it were adapted from my book, Quest for the Presidency: The Storied and Surprising History of Presidential Campaigns in America (Lincoln, Nebraska: Potomac Books/University of Nebraska Press, 2022).

And don’t forget to subscribe to The Riel World if you haven’t done so already.

(Photo credits: Burr-Hamilton duel, Thomas Jefferson, Aaron Burr, and John Adams, all from Wikimedia Commons.)

Excellent job filling in the details, Bob!